Author Backgrounds:

Mohnish Pabrai is the Managing Partner of the Pabrai Investment Funds and Dhandho Holdings. Since inception in 1999 with $1 million in assets under management, Pabrai Investment Funds has grown to over $690 million in AUM with an annualized gain of 17.7% (versus 5.2 % for the Dow). He is the author of two books, including The Dhandho Investor. Mohnish is also is the Founder and Chairman of the Dakshana Foundation, which is focused on providing world-class educational opportunities to economically and socially disadvantaged gifted children worldwide.

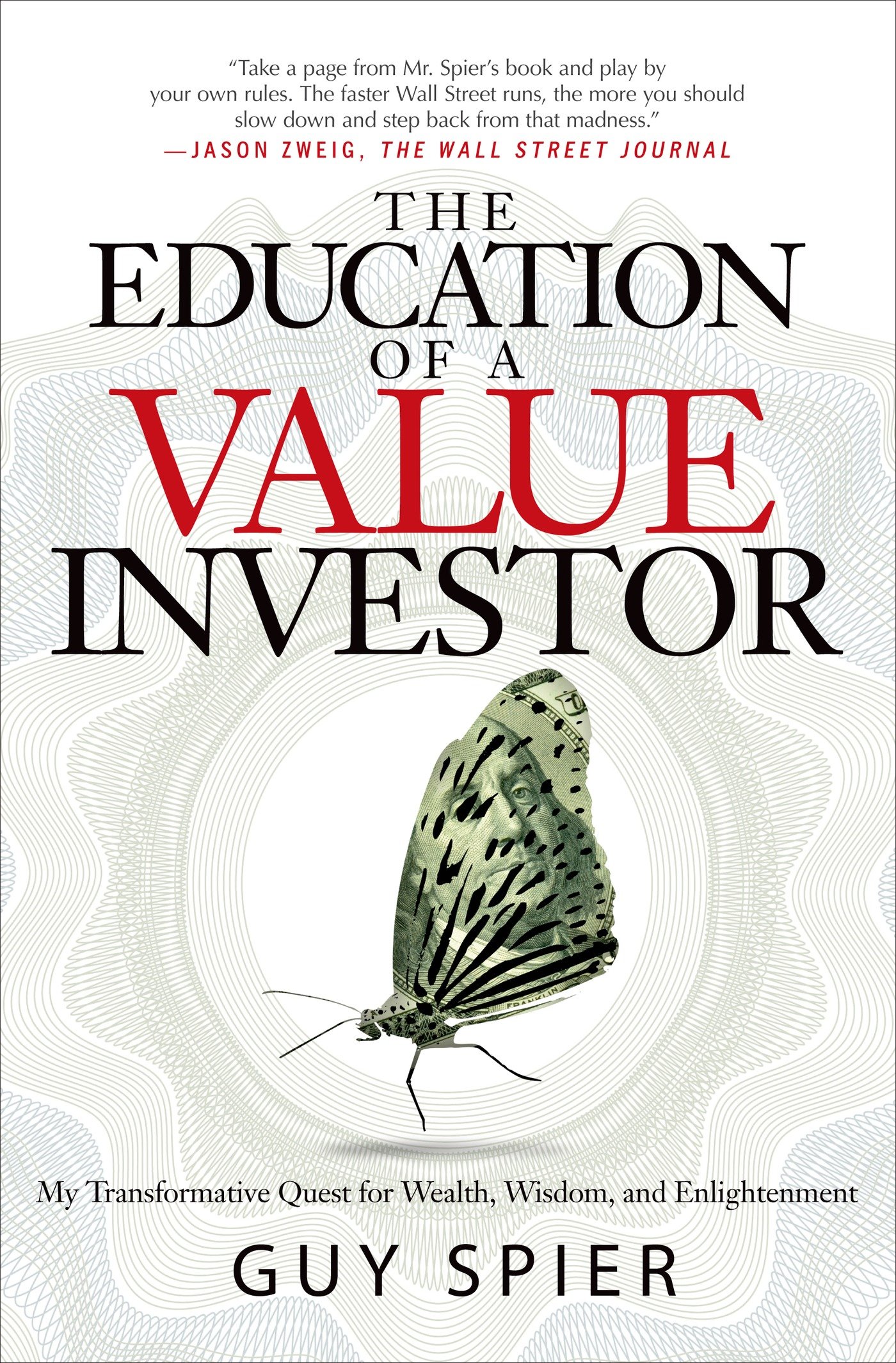

Guy Spier is the manager of Aquamarine Fund, an investment partnership inspired by the original 1950’s Buffett partnerships. In 2007 he made headlines by bidding $650k with Mohnish Pabrai for a charity lunch with Warren Buffett. Guy recently published his first book, The Education of a Value Investor. In 2009, Spier and his family moved from New York to Zurich, Switzerland to escape the noise of Wall Street. He attained his MBA from Harvard Business School and has a First Class degree in Economics from Oxford University. He spoke at TED India and co-hosted TEDx Zurich.

Guy’s Book Recommendation:

Audio Podcast:

Other ways to listen:

* On iTunes

* Right Click + Save As to download as an MP3

* Stream here directly

With gratitude,

Transcript:

Jake: Welcome to Five Good Questions. I’m your host, Jake Taylor. We got a special treat for you today. Both Mohnish Pabrai and Guy Spier are here to talk to us.

Mohnish is the managing partner of the Pabrai Investment Funds and Dhandho Holdings. Since inception in 1999, he’s grown $1 million in assets under management into over $690 million with an annualized gain of over 17% versus 5% for the down. He’s the author of two books including the Dhandho Investor.

Mohnish is also the founder and chairman of the Dakshana Foundation which is focused on providing world class educational opportunities to economically and socially disadvantaged gifted children worldwide.

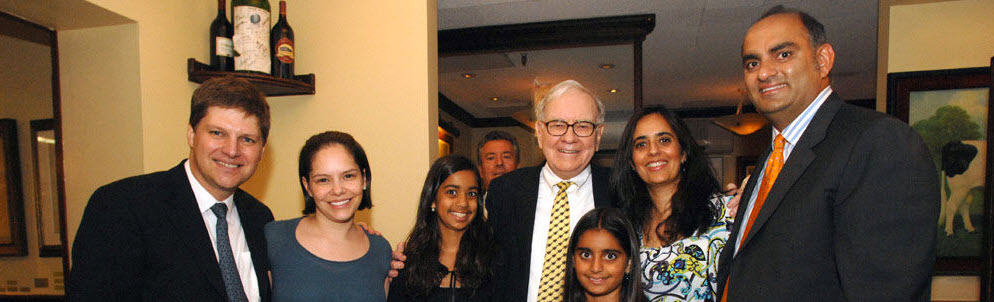

Guy Spier is the manager of the Aquamarine Fund, an investment partnership inspired by the 1950s Buffett partnerships. In 2007, he made headlines by bidding $650,000 with Mohnish for a charity lunch with Mr. Buffett. He attained his MBA from Harvard Business School and also a first degree in Economics from Oxford. He now lives in Zurich with his wife and 3 kids.

Guy recently published his first book, The Education of a Value Investor.

Here’s part one of two of our interview. Enjoy.

Welcome, everybody. We are going to have a special treat for you today. We have two premier investors that we’re going to talk to, Mohnish Pabrai and Guy Spier. Guys, we really appreciate you coming on the show today. It’s really a big pleasure of mine. You guys are two of my biggest heroes. So you guys got to talk with Mr. Buffett over lunch and this is like my mini version of it. Although I think I pay a little bit less than you guys did.

Okay, so guys ready we’ll just jump right in to our questions here. And this is going to be the first part of a two-part series so just so everyone knows.

Question #1 is both of you use a very unique structure for your funds that you manage. Where did you guys find that structure and why do you think that it’s so special? And really how has it allowed you to be so successful?

Guy: I do not have a pure naught percent management fee and 25% of the profits structure eventhough I’ve read that Warren Buffett had done that. I had to meet Mohnish Pabrai where I saw that structure and I heard him talk about it. Now I have to listen to him talk about it for about 5 years until I implemented that in my fund. And even then, I implemented it in a way that left the existing investors and the existing arrangements intact.

So eventhough I’d read all about Warren Buffett, I did not fully understand the importance of cloning that fund structure utterly accurately. So I had started feeling the benefits of that structure only over the last 5 years or so as the proportion of the investors who invested in that share clause have increased in the fund. And I will tell you that it is absolutely extraordinary because there were some benefits to it that I would never have predicted. I think that the people who invest in that kind of fund where they say, “I’m not paying the manager a fee, I’m only paying him a portion of the profits” is a very special kind of person. And so, for example, one of the benefits is that I almost never go on marketing calls. But let’s see what Mohnish has to say, I’ll stop now.

Mohnish: Basically, the structure was copied from Warren Buffett. And I copied the structure in ’99 when I started because I had never worked in hedge fund industry. I wasn’t even aware fully of the hedge fund industry. I wasn’t even fully aware of the rules. I was very familiar with the Buffett partnerships. Those rules intrinsically made a lot of sense to me. And so I mindlessly cloned those rules of the zero percent management fee, 6% hurdle, one-fourth or 6%, because all of that made sense to me to be an alignment with investors and not talk about holdings and so on.

And it’s only a few years after the funds were up and running that it dawned on me as I was seeing the power of that model that for a small sliver of humans. What I would call a small sliver of enlightened human. Those rules are quite important. And they’ve helped the funds grow in scale and be an alignment with time as a result.

Jake: So you would say probably one of the best things is that you get a class of investor that you wouldn’t have otherwise been able to get, basically. Or at least you attract the right tribe to what you’re all about.

Mohnish: I mean I think that basically if you’re at McDonalds offering a certain type of service. You’re going to attract a certain type of clientele. And if you’re fine dining at a French restaurant, you’re going to attract a certain type of clientele. And the fine dining French restaurant patron going into McDonalds may not be that happy.

So basically, any business with the way it sets itself is up is naturally, basically aligning itself with a certain clientele. So Pabrai funds is very unattractive to institutional investor. It’s very unattractive when there are consultants involved. And it’s generally attractive when there’s typically a principal those generation. Entrepreneurs have created their own wealth. Who actually spend the time to do their research, understand a few of the nuance so that then proceed to do invest. Of course, my job over time is to kind of help educate them about some of that.

And so we end up with what I would call almost an ideal investor based from that vantage point.

Jake: That’s great. Question #2, you guys are famously paid almost $700, 000 to have lunch with Mr. Buffett as a way of giving back for all the amazing things that you’ve learned from him. One of the, I think, biggest takeaways that I’ve1 got from hearing you guys talk about it in different venues was the idea that you have this inner scorecard and that Mr. Buffet is very good about having and following his own inner scorecard.

And I think that that’s something that is very difficult to I want you guys to take on that’s an innate trait or is that something that can be developed, having more of an inner scorecard because it’s much easier to say it than it is to actually do it.

Mohnish: I’ll get started first and then hopefully Guy can chime in later. Well, you know I think that when we are young children. I’m saying children under the age of 5, for example. For the most part, they’re in alignment. And for the most part children are, at that age, almost complete the inner scorecard. They tend to, especially we got the three years olds inner scorecard, they tend to, you know, go with what make sense to them and so on.

And over time what happened is that society imprints a bunch of its accepted norms into the child’s psyche and brain and so on. And over time, from my vantage point, more and more gunk gets added, into taking the person of equal alignment into what is called socially acceptable responses, kind of more diplomacy over truth and this is the way you’re expected to act and all these sorts of things.

So I think the humans create whether they’re in natural state of humans to be aligned and inner scorecard focus. I don’t think it is a very big stretch or difficult job to get there as an adult even when 15 or 17 years or several decades of gunk thrown at you. But one has to make a deliberate effort and one has to be willing to take the pain. And willing to go into what may not be in one’s comfort zone.

And you know, one thing that my younger daughter who was at the Buffett lunch. And at the end of lunch, I asked everyone I know what they thought of the lunch. I think she encapsulated the lunch perfectly in one sentence. She said, you know, he’s just a kid. And my impression of Buffett was that Buffett was like a 5 year old.

And I think that is probably the absolutely best description I ever heard of Warren Buffett. Because Buffett retains, you know, he actually said at the lunch that he eats only what he used to eat at 5 years old. And so he retains the innocence, the purity and the forthrightness of a child. And the inner score card I think with someone like Warren Buffett comes in naturally because of those child-like traits. And for the rest of us, I think it’s more work. I think he’s been practicing it for so long that it’s a natural way. Charlie Munger is that way. In a more abrasive way, I think Warren has a veneer of diplomacy.

But I think the inner score card is very much something that people can make a core part of who they are. But it requires a deliberate effort and putting it front and center to make it happen.

Guy: I just riff on a couple of things. You know my children have been on a Montessori School now for the last few years as I believe Mohnish’s children were. And Larry Page and Brin. I think Montessori education by allowing the child to find out what truly makes them shine and what they enjoy as a way of developing the inner score card.

But I would tell you that our extremely powerful forces in society. For example, anybody who’s been through any kind of a lead educational system has been made to take exams and so much depends on what grades you get in the exams. All we spend all these time figuring out how to do well in those exams and meet the approval of others in all sorts of ways. And there some elements of the world which are just by nature outer score card. Exams are one, promotions are another. A third one that came up in a question to me are the stock market industries.

So it’s not as if I could’ve underperform the standard and pulls for five years and then to say of “Oh, but that’s an out of school card thing.” I will just focus on my inner score cards. Now there are some hard boundaries there. But what I would tell you in my experience is that, you know Jake, it doesn’t matter. I do believe some of it is innate. I think there are certain people, certain personalities, who just listen inside more. And I think that Warren Buffett and Mohnish Pabrai are two of those. But you know what? We can change that. And so I think that I’m somebody who whether by nature because I do like to seek the approval of others or through the educational experience that I have had a tad in the past are a much stronger orientation to outer score card.

And the key thing is there are so many things that we can do to make us more inner score card focused. For example, the kinds of friends that we have. If we have friends who are focused on outer elements of success, signs of success; it’s just, we will absorb that and we’ll end up doing that ourselves. But if I show up with somebody like Mohnish, you know I really care how many books I sold. He will indicate to me how I’m kind of focused on the wrong things.

So I think that building our environment, putting ourselves in the situation where we can learn listen to that score card is huge. And I think that we can make, all of us, can make progress in that direction.

Jake: That’s great. I didn’t know that you guys were both Montessori fans. That’s interesting because I have that same experience. I had learned a bunch of, you know, like Larry Page and Jeff Bezos; all these guys were Montessori kids. And I got to the wondering what was going on with that. I’ve read a couple of books about it. And now both of my boys are in Montessori programs so that’s cool to hear that.

Guy: You look like you’re far too young to have children. When I was your age, I didn’t even know what marriage was but.

Jake: I’m figuring it out the best I can. Okay so let’s go to question #3. And this has to do with, this is a little bit more investing related. I don’t know if you guys follow a lot of these but according to a lot of macro valuations whether it’s Market Cap to GDP which Buffett has said was said one of this favorite indicators, Tobin’s Q and Shiller PE. There’s a lot of elevated value at the moment. And another key thing about that is that the dispersion is relatively tight around that high mean.

So basically it’s kind of hard to find good investment ideas at the moment with where the markets are historically. Is that ringing true for you guys at all right now as far as what you’re saying? Are you guys finding value anywhere or are you like a lot of people that I’ve talked to that are kind of waiting on the sidelines at the moment for some better valuations to come along?

Mohnish: I’ll start. You know, as someone who I don’t endorse but who says there’s always a bull market somewhere which is our friend, Jim Cramer. I think there’s truth to that. I mean I think that they are like 50,000 publicly traded stocks around the world. There are commodities; there are other asset classes and so on. And the world is continuously going through different levels of turmoil that, you know, areas of euphoria, areas of panic and so on. So there are always opportunities around. It’s a question of whether one is aware of them, whether something is within circle of competence and all those things.

So the way I approach investing is you know, first of all, that Market Cap to GDP number. Something I have never understood is I’ve never understood why Market Cap to GDP had anything to do with the price of tea in China. And the reason is that if you told me it is business valuation of every business in the United States to GDP, that I think I can understand. But Market Cap to GDP is only looking at those businesses that are publicly bidded. So if you’re in a situation where there are a few public companies versus many public companies so that number will move around. So I never understood why Warren pays attention to it, he’s a lot smarter than me so there would be good reasons for that.

But to me, there is no point. I don’t even know where the number is right now and I quite frankly couldn’t care less what that number is. I don’t care what the sugar numbers are. I don’t care what any of these macro numbers are and I couldn’t quote them for you. I have no idea about them. My take is that when a specific business you’re looking at as a value that hits you in the head with like a 2×4 then you don’t need more than 3rd grade math. Where the P is 3 or something and it’s blindingly obvious that it’s within your circle of competence then you should act. And in almost all of the circumstance regardless of what Shiller is saying, all those ratios of Market Cap to GDP is saying; you should not act. So it gets down to specific businesses and whether you can understand the business so that what you think they’re worth and what they are really looking for.

Jake: Let me add a little bit of nuance to the question. I think what I’m getting at is that there’s times where it’s obvious that it’s a great time to be fishing and there are other times where it might not be as obvious. And I wonder if sometimes with the way that the human mind works about like talking to yourself into seeing values sometimes that you might be better off taking a vacation when valuations across the board are generally high. It’s probably not a great time to be really digging through potentially. That’s kind of what I think I’m getting at.

Mohnish: Well, my answer and, you know, certainly I’d like to hear Guy’s views. But my answer is that first of all, there’s a need to cull the data set. The data set is too large at any time whether the markets are undervalued or valued. The data set is too large to cull through or to go through. And a great way to cull the data set is to be a shameless cloner.

And so, you know, identify then 10, 15, 20 investors. Look at the top 3, 4, 5 holdings. Look at the ones that you think are within circle of competence. Look at the ones that you think are cheap. That’s a pretty quick list to go through. And if you go through that and if you find there’s nothing to do then certainly go fishing, no problem. Or in Guy and my case, go biking.

And if you find there’s stuff to do in that space then, by all means, go ahead. But I don’t think one should take a mindset of “all markets are overvalued, there’s nothing to do.” Pabrai Funds started in July of ’99. And you know, I think the first twelve months, we were up more than 70%. And that included the implosion of the NASDAQ in March. And in fact, for the first 8 years of the fund, we never had a downhill. And so, you know, 2000, 2001, 2002, these were terrible years for the stock market if you were invested. But we had no problem finding things to do and generally good returns. So in fact, that was a time when the dark ones are sucking so much money out of the rest of the economy that, you know, things that Berkshire Hathaway and others gone really cheap. So you were able to pounce on those. I would say that today if you had the stomach to look at the stocks in Iraq and Syria and those wonderful geography is, I’m sure you find some stellar bargains in different asset classes there.

Guy: I propone those geography is, Jake. I was this weekend in Malta and Malta is very first close to Libya. And I can tell you a number of business people who own all sorts of businesses in Libya. Now, many of these were private businesses. But that’s some extraordinary opportunity in Libya right now. I think that, you know, everybody always says that then it was easy and now it’s hard. And I would tell you that sit around waiting for a time when the world is in panic like in 2008, the vast majority of people are beset in those periods with other problems. Like they have a lot of redemptions from their funds or they’re getting fired or there are all sorts of other turmoil that prevent them from investing.

And I was just thinking as Mohnish was talking. Imagine if you’ve watched sumo wrestlers, you know the actual bout of interaction with the other sumo wrestler is such a miniscule proportion of their lives. And even such a miniscule proportion of the time that they are actually being watched by the video cameras, all the rest of the time is preparation. And I think that rather than, from my perspective, worry about whether the markets forever undervalued, it’s a case of constantly working the way those sumo wrestlers do on their preparation for that bout that may be a miniscule and very, very short period of time. And I think that you in asking that question as well as many others, we go straight into that rational neocortex.

And the rational neocortex is mush in relation to many hard problems in the world. I think that training involves working on our own thoughts about risk, working on how we process information, identifying managers, identifying businesses. And that’s our equivalent of the kinds of things that sumo wrestlers do before they actually get into the bout. And so focusing on whether markets forever undervalued or that it’s hard to find value right now is a kind of a distraction in a certain way.

Jake: That’s really interesting point. I like that. And I’ve read a quote, I think it’s a Navy Seal saying that, “The more I sweat in peace, the less I bleed in war.” So maybe that’s kind of fits in with what you’re saying.

So this next question #4 is for you, Guy, primarily and it has to do with your book. And I just wanted to give you a compliment that I found it to be amazingly honest and you really let your guard down which I had to give you a lot of kudos for that. You know you could have very easily just talk about your lunch with Buffett, your relationship with Mohnish and called it a book and, you know, send it off to the publisher. What was it that really drove you to be so disarmingly open?

Guy: Oh, thanks for the compliment. I just want you to know that I think that I would not have been able to produce a book of that quality on my own. I had some extraordinary help from a great editor and two collaborators. An early collaborator named Jessica Gamble and the late collaborator named William Green. William Green is actually now writing a book on some great investors. It’s going to be a beautiful coffee table book. He’s well worth following.

But the interesting thing is that if I had not met Mohnish Pabrai, I don’t think I would have written the book and for multiple reasons. First of all, you know, you get better when you get around people that you like and admire. And getting around Mohnish and seeing that he had published two books, I’ve sort of created or increased the appetite in me to do that. But it was also through Mohnish that I ended up attending the TED conferences. And one of my collaborators I met at the TED conference. And another organization that helped me tremendously was YPO. And it was because I was around Mohnish that I joined YPO.

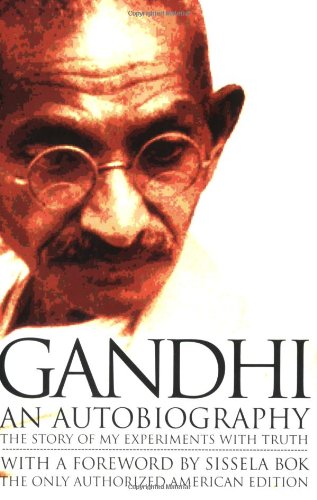

But then the other thing that happened which explains this desire to let down ones guard is that if you get around somebody like Mohnish Pabrai, he’s all about authenticity. In fact, he has no patience and no interest in being around people who don’t already have a high degree of authenticity and are hopefully getting more authentic. And the two most profound ways that came across to me was the autobiography of Mahatma Gandhi that Mohnish had mentioned to me. And also this book, Power versus Force.

So when I got to writing, you know, that was a goal for me from the very beginning that this was going to be an exercise in trying to be as honest with the world as Mahatma Gandhi was in his autobiography. And the key thing about his autobiography which utterly struck me when I read it is that, this is his one and only autobiography, and he talks about having sex with prostitutes. And he talks as a devout Hindu. Having grown up in a devout Hindu family, he talks about eating meat. And he cares so much about eating meat that another point in the book we discovered that he may have been more willing to see his son die from being ill because of not eating meat than to eat meat. He cared very, very much about humans are harming other forms of life deliberately. And he writes about that openly.

And I think that that inspired me to want to do the same for me almost as a life experiment. Because actually when we lower our guards, as you put it, and we actually have nothing to fear from the world and that’s something that I would tell you. I mean, it’s funny that you should use the words “lower my guard” because, in a certain sense, I didn’t lower my guard. I opened up and I’ve received an awful lot of love from an awful lot of people for having opened up in that way. And I would encourage you and others to do the same.

Jake: Very powerful. Thank you for sharing that. Question #5 is, this has to do with investing moats. There’s been some interesting research today that I’ve seen recently that points to the underlying business economics, the moat, the high returns on invested capital, also tends to being revert. And that make sense if you think about it from a microeconomic standpoint, you know, a lot of honey will attract a lot of bees and it will drive down returns for everybody in that industry. So it would seem that moats are maybe not that hard to find but they’re very hard to find the ones that are going to still be around, the sustainable ones.

Now, obviously, Buffett has been very good about finding these sustainable moats. And my question is do you think that that is only because he’s read so many books over the years that he knows, he can recognize what will be a sustainable moat? And if that’s the case then is it the implication for us who haven’t read as many books that maybe we are not going to be that good at finding moats and maybe we should be thinking about looking for other advantages like maybe mostly based on how cheap we can find it? I mean, what are you guys thoughts on that?

Mohnish: Do you want me or Guy to answer it?

Jake: I’d love to hear from both of you.

Mohnish: Okay, yeah. So let me get started. So first of all, the investing business is an extremely forgiving business. You know, John Templeton used to say that the best investment analyst is one who will be right more than 2 out of 3 times so a 33% error rate. If you actually hit a 33% error rate, you hit the ball so hard at the park that you know you’d be Buffett-esqe in performance.

And so even if you get someone like Warren Buffett who is exceptional investor probably the best investor in the history of mankind; Buffett’s track record if it’s segmented by industry, you’re going to find very wide variations. So let’s say Buffett in banking industry, no errors. I am not aware he’s been making investment in banks since 1969 so like 45 years of bank investing. I am not aware of a single bank investment he’s made where it has not worked out at least as well or better than he thought.

Jake: Maybe Solomon?

Mohnish: No, I’m talking about commercial banks.

Jake: Oh, okay.

Mohnish: Yeah. So investment banking is really a different animal. But commercial banks, his investments in consumer and commercial banking is a batting average of a thousand. It’s a perfect batting average. So he’s an exceptional banking analyst probably the best banking analyst on the planet. But then on the other hand of the spectrum, if you look at Buffett, the retail analyst, it is a horrible track record. In fact the track record I would say may not be more than 20, 25% are correct and, you know, 75% of being wrong on the business.

So you know, Borsheim and Nebraska Furniture Mart had both been I think homeruns. But almost every other furniture operation they’ve bought and these were bought after having Nebraska Furniture Mart, after having the Blumkins on board. After having the Blumkins chimed in on their perspective. In fact Jordan’s furniture, for example, was recommended by the Blumkins, horrible investment for Berkshire.

So if we look at their furniture investments, if we look at all their jewelry retail investments; two areas where they have no expertise before they went in, they have been terrible track record. Insurance, it’s hit or miss. You know some have worked very well and a lot of it have not. So eventhough we think of Warren Buffett as the master of insurance.

And so the good news of that is that here we have even the greatest investor of the world with lots and lots of mistakes in all other place, you know, even in manufacturing Dexter shoes, you know, NetJets and so on. So there are lots of mistakes all over the place but still an incredible track record. And that’s what’s exciting about his business is that you don’t need to be right all the time. And he has moats. Moats don’t last but sometimes there are some moats that can last a really long time.

So for example, one of the questions we asked Warren Buffett during our lunch with him was, my daughter asked him, you know, what’s his favorite business out of all the businesses that Berkshire owns. And he didn’t even hesitate for two seconds, he said it’s Geico. And I think the reason he likes Geico is because that moat has only been widening from 1950 till today. You know it’s a 50, 55 years, 65 year run. Actually it’s almost a run from the founding of Geico, you know, right from the beginning. They had a couple of hiccups along the way but pretty much the more the moat has widened almost throughout. When the internet came along, it dramatically widened the moat.

And at some point when we have driverless cars, that moat is going to disappear. But we’re quite away from there. But you can actually get once in a while. You don’t need that many in a lifetime. You can once in a while get some pretty long runways with once.

Guy: Yeah. But you know, I don’t know if this is helpful and look Warren Buffett is smarter than I am. And he has read an awful lot more than I am and he’s probably an awful lot harder working. And those are all things that I can’t change. I think that one question that is really worth asking, I don’t know why it took me so long to figure out, is I think it was asked by Warren first; is the moat getting wider or narrower? And it’s just asking that question, under what rate is it getting wider or narrower. If you think there’s a lot of sort of a second order of margin of safety in investing in a moat that’s clearly getting wider.

And then if you ask, you know, something like in any business is a new development a tailwind or not. Mohnish just identified how frivolous cars where as they get safer and safer will actually be a negative for Geico’s business and over what time span they emerge. Then we can answer a lot of questions.

And you know, I also don’t think that you should rule out that you or anyone of your contemporary will uncover business moats widening and profound business moats sooner than the rest of us. I mean, you know, I’ll just give you the two examples. There’s a business called Horsehead Holdings that I think it has a growing moat. And it’s something that many people aren’t aware of because it’s kind of been growing over the last 20 years. I will leave you to do the research and figure it out.

Or another company that only emerged recently called Verisign. And Verisign seems to have an incredible moat around a very unusual business which is internet registrations. Although these things do appear from time to time and there’s no reason why we have to wait for Warren to uncover them. They may be incurring in smaller industries and we’re the only ones positioned to find them. So I don’t think one should give up on that.

Jake: That’s great. Let’s wrap up part one here and I want to get a book recommendation from you, Guy, first. And then we’ll close with that. What’s a book that you’ve given away a lot or that you feel like is underrepresented out there kind of a hidden gem. You’ve mentioned Gandhi’s autobiography earlier and that’s a perfectly valid choice. But I’m curious to hear what you would come up with.

Guy: I mean, I will just tell you something that’s really important I think is that, you know, I can throw out a book and it just may not be right for you at that particular time. I left that first meal with Mohnish and I went on to my Amazon account and purchased Gandhi’s autobiography. And it sat on my bookshelf for I don’t know how long until I read it. And so I think it’s really important.

And there’s another thing that I kind of feel like taking but you need to allow serendipity to strike. And insights come from all sorts of unusual cases. I was just telling somebody the other day that there’s a book that I read called City Police where a historian from Harvard went and embedded himself with the New York City Police force to see what actually happened on the ground. And then wrote about his experiences. And you see how the press and how a perception of the police is so different from what actually happened on the ground. And it really gave me a much better understanding of how different the view of a company’s management is from the investor perspective than what they actually see.

But with that in mind, I just got an email from somebody. I think that a book that really struck me that everybody ought to read is a book called Different: Escaping The Competive Herd by Youngme Moon. I think that explains an awful lot of Mohnish Pabrai’s business strategies. He seems to have an innate way of… I would tell you that I’ve seen him appear at conferences as everybody’s dressed in a blue shirt, he’ll dress in a yellow shirt. It’s just he doesn’t consciously think about it. But I think that opened my mind up to a lot of sort of contrarian type thinking that I wouldn’t have been open to before. But I think that most important and it really is. I feel like I do best when I pick up unusual books that have caught my eye for no good reason because it’s serendipitous what I will pull out of it.

In fact, so just to tell you, I don’t think that having and read this is a good idea. It’s like going to the library and see what captures your eye and different people should be different, reading different things at different times.

Jake: That is one way to probably differentiate your research from everyone else’s. So that wraps up Part One for us. Guys, we’ll see you; everybody, we’ll see you in next week for Part Two.

Guy: Jake, I want to hear Mohnish’s book pick. I want to hear what he has to say to that. Can we hear him on that?

Jake: That will be on Part Two next week.

Guy: I see, okay. No comments from him right now?

Jake: Not yet.

Guy: I want to hear from him. Can we just get some comments? Mohnish, what do you have to say to that?

Mohnish: We’ll wait till next week. And if you’re around in an hour, Guy, I’ll call you.

Guy: Right, I will be looking forward to it.

Mohnish: Okay.

Guy: Jake, thank you very much. This has been fun.